Standardized testing is a controversy in American education for many reasons, one being that it poses a variety of problems for English Language Learners. Preparation inside the classroom for ELL students is also faced with its own plethora of difficulties both pedagogically and socially. Academically, ELL students are challenged with many disadvantages in comparison to their English-speaking classmates including, for example, differing starting points. In addition, ELL students are also faced with having to make sociocultural adjustments. Standardized testing as a means to measure student’s progress is necessary but the requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act including high stakes accountability, the unilateral techniques used for the standardized tests and their grading methods are all poorly devised concepts behind standardized testing.

Under civil rights law, schools are obligated to ensure that ELL students have equal access to education. Standardized testing as a measurement of student’s learning progress alone would be debatable as there are many ways to teach and assess student’s advancement in the education setting especially for ELLs but given the high stakes that are paired with the test’s average outcome has only increased the level of difficulty for students and teachers. With a continuing rise of ELL students in American classrooms, various teaching methods are being explored but students are expected to learn English and content very quickly and are then issued a standard test to measure their achievement. Students are all different and teaching ELLs must include differentiated instruction so it seems that the standardized tests are not very accurate means of evaluation. An equal education should be to prepare all students to perform in their future roles necessary to the social, political, and economic functioning of society; preparation for the exam itself, however, has taken an important role inside the classrooms using various, often conflicting and highly debated methods.

As mentioned above, there have been numerous education methods practiced for ELLs. The submersion method (using a sink or swim approach) proved to be a failure because while students with little English skills were provided with the same facilities, textbooks, teachers, and curriculum, they could not understand the language they were being taught in and therefore they were not given a truly equal education. In 1974, the case of Lau v. Nicols in which Chinese American students with limited English ability asserted that they were not getting the help they needed and were entitled to because of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ban on educational discrimination on the basis of natural origin. “Within weeks of the Lau v. Nichols ruling, Congress passed the Equal Educational Opportunity Act (EEOA) mandating that no state shall deny equal education opportunity to any individual, ‘by the failure by an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by students in an instructional program.’ This was an important piece of legislation because it defined what constituted the denial of education opportunities” (NCELA). Since the ruling, while educators are aware of equal educational opportunities, there has not been a specified program or strategies issued by the Department of Education or the Office for Civil Rights to teach ELLs.

This submersion method and the following methods correlate with several attempts throughout American history for an English-Only movement which advocates that English be the official and only language used in the United States. In his book, Language Loyalties, James Crawford summarizes the opposing views on this topic, as follows:

Arguments against the English-Only movement include the idea that it threatens to inhibit the academic advancement of many language minority children, and also deprives these children of the many social advantages resulting from using their mother tongue (Lu). The identity and language of education establishes an understanding and relationship to the social world. The classroom community and learning methods for English learners help the student to create an identity. While the federal government has never imposed legislation mandating an official language, state-imposed standards require schools to provide language minority students with inappropriate instructional programs (Lu).“For supporters, the case is obvious: English has always been our common language, a means of resolving conflicts in a nation of diverse racial, ethnic, and religious groups. Reaffirming the preeminence of English means reaffirming a unifying force in American life. Moreover, English is an essential tool of social mobility and economic advancement. The English Language Amendment would "send a message" to immigrants, encouraging them to join in rather than remain apart, and to government, cautioning against policies which could retard English acquisition.“For opponents, Official English is synonymous with English Only: a mean-spirited attempt to coerce Anglo-conformity by terminating essential services in other languages. The amendment poses a threat to civil rights, educational opportunities and free speech, even in the private sector. It is an insult to the heritage of cultural minorities, including groups whose roots in this country go deeper than English speakers--Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and American Indians. Worst of all, the English-Only movement serves to justify racist and nativist biases under the cover of American patriotism” (Crawford, 1992, p. 2-3).

Schools explored the bilingual education model in which students are taught content using both their native language as well as English. There are several bilingual education programs, two of which are English as a second language in which ELLs and native English speakers are taught together in English throughout the day with the ELLs having an extra pull-out tutoring session; and transitional bilingual education which works to ensure that English learners do not fall behind in content areas such as math, science, and social studies so they are taught the content in their native language with English being taught as a separate subject (Rossell). The goal here is to increase their competency in English over time while developing literacy in their native tongue to ultimately mainstream them into English only classrooms. This way, they progress academically at the same rate as native English-speaking students so when they become proficient in English, the content is easily translated.

Other methods for bilingual education include the Paired bilingual education (also known as Dual language immersion) and Two-way approaches. “Paired and Two-way bilingual programs are very similar. They both comprise of alternate teaching between ELLs' native language and in English at different times of the day from the beginning of their education. The difference is that two-way programs also teach a second language to native English speaker” (University of Michigan).

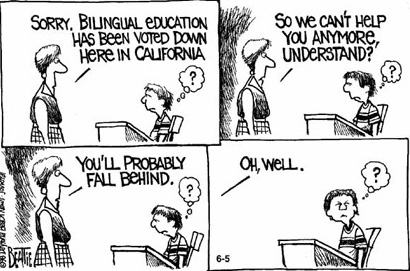

In 1998, “Ron K. Unz, America’s most successful opponent of bilingual education,... originated Proposition 227, a 1998 California initiative calling for the outlawing of bilingual schooling and its replacement with a one-year ‘sheltered immersion’ program to teach English to immigrant students” (Newsmax). Sheltered English Immersion means that “nearly all classroom instruction is in English but with the curriculum and presentation designed for children who are learning the language” (Massachusetts Department of Education, 2003, p. 7). The problem with this method is the idea that ELLs can learn the sufficient amount of the English language in one year while also learning content even though teachers are only teaching the content in English and not teaching English as a second language. According to Kevin Clark in his article, “The Case for Structured English Immersion,” he states that one of the reason why schools implement SEI is because “most state student performance assessments are conducted in English, and schools or districts that miss targets face increased scrutiny and possible sanctions. This provides added incentive for schools to get students' English proficiency up to speed as soon as possible.”

The current debate in education regarding ELLs is whether to implement bilingual instruction or sheltered English instruction. With the No Child Left Behind Act’s added pressures of standardized testing, more states are beginning to follow the SEI method. This is a dangerous trend for students. According to James Crawford,

Aside from the academic challenges English-Only methods present, “when a school reinforces an English-Only policy, it sends a message to all children that minority languages have less value than English as tools of learning. And because the school is a microcosm of society, this message also suggests that those languages are not an integral part of the American society” (Lu).“There is no credible evidence to support the "time on task" theory of language learning; the claim that the more children are exposed to English, the more English they will learn. Research shows that what counts is not just the quantity, but the quality of exposure. Second-language input must be comprehensible to promote second-language acquisition (Krashen, 1996)...Time spent learning in well designed bilingual programs is learning time well spent. Knowledge and skills acquired in the native language, literacy in particular, are "transferable" to the second language. They do not need to be relearned in English (Krashen, 1996; Cummins, 1992). Thus, there is no reason to rush limited-English-proficient (LEP) students into the mainstream before they are ready.Research over the past two decades has determined that, despite appearances, it takes children a long time to attain full proficiency in a second language. Often, they are quick to learn the conversational English used on the playground, but normally they need several years to acquire the cognitively demanding, decontextualized language used for academic pursuits (Collier & Thomas, 1989).Bilingual education programs that emphasize a gradual transition to English and offer native-language instruction in declining amounts over time, provide continuity in children’s cognitive growth and lay a foundation for academic success in the second language. By contrast, English-only approaches and quick-exit bilingual programs can interrupt that growth at a crucial stage, with negative effects on achievement (Cummins, 1992).”

Because The United Stated has not declared English as an official language but it is the most commonly used language on an international basis in terms of science communications and the Internet, for example, many non-English speaking people may consider the prevailing of the English language more of “a problem of linguistic hegemony. It is evident that English is the de facto international language of international communication today, but it is also evident that the dominance of English today causes not only linguistic and communicative inequality but also the feelings of anxiety and insecurity especially on the part of the non-English-speaking people in a rapidly globalizing world in which English dominates extensively” (Tsuda).

Because the No Child Left Behind Act puts such emphasis on standardized tests which are only given in English, standardized testing and preparation for the standardized tests are setting up ELLs for failure. Test bias, regardless of test preparation, hinders students ability to score highly on standardized tests. For example, ELLs, whether being taught the English language in a bilingual setting or in SEI, will undoubtedly have difficulty understanding “test language.” In addition to testing content knowledge, standardized tests are also measuring reading comprehension by employing unnecessarily complex language. So while ELLs may prove to be English proficient in class regarding their understanding of the content, the complicated “test language” is confusing to ELLs; they might know the content but they simply do not understand the question.

Take Krashen’s Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis and Jim Cummings’ distinction between basic interpersonal communicative skills and cognitive academic language proficiency for example. In class, teachers employ many tactics to educate ELLs through differentiated instruction; the use of visual and auditory aids, for example, may help ELLs whose English skills may be at a lower level in reading and writing. So, while the student may have a concrete understanding of the course content, they can only showcase their comprehension through their basic communicative skills without focus on form. Test bias not only affects ELLs but most minority students as well. The United States is incredibly diverse and yet schools are requiring all students to meet the same standards and pass the same test.

NCLB and SEI does not take into consideration that ELLs are a very diverse group in terms of socioeconomic status, linguistic and cultural background, level of English proficiency, amount of prior education. Students who have transferred from a school in their native country with a high level of education and a student who received little education in their native country cannot and should not be in the same classroom because those students are on completely different academic levels. Students with varying levels of established English proficiency would hinder classroom instruction when some students could benefit from advanced English and others require slower, lower levels of English instruction. In addition, putting students with differing English skills goes against Krashen’s theory of second language acquisition, it would be inevitable that some students would fall behind while others would be employed to help or tutor.

Socioeconomic status and cultural background are two areas in which No Child Left Behind does not take into consideration and diminishes ELLs and other minority student’s opportunity for equal education. Students are subjected to face forms of racism and lingo-racism in their schools. Not only are children supposed to learn academic content but they are also expected to learn in (and adapt to) a new cultural context.

In a recent Forbes article by contributor, Gene Marks, entitled, “If I Was a Poor Black Kid” he complains that minority children just aren't working hard enough. ‘If I was a poor black kid I would first and most importantly work to make sure I got the best grades possible,’ writes Marks, a self-described middle-class white accountant. “I would make it my #1 priority to be able to read sufficiently. I wouldn’t care if I was a student at the worst public middle school in the worst inner city. Even the worst have their best.” Marks is claiming that minority students are slacking academically because they are lazy and “it takes a special kind of kid to succeed.” Implying that minority students have to be special to succeed is insulting and proves of his own ignorance or unwillingness to admit that the rules have been stacked against minority students.

When an English-learner asks the teacher if (s)he can go to the bathroom and the teacher, trying to use every opportunity to support standard vocabulary and sentence structure comprehension as the student’s might see on the standard test, answers the student by correcting his/her question with, “you mean, ‘may I go to the bathroom,’” (s)he has just confused the student and most likely increased the student’s affective filter by correcting a phrase commonly used and previously thought to be correct by the student (when in actuality, that student was using “can” in its secondary model form as a verbal modifier asking for permission, as opposed to expressing an ability (so (s)he was right all along).

Other minority students are faced with the same lingo-racism in classrooms. For example, African American vernacular English (or Ebonics) has not officially been considered its own language but poses some issues in the academic setting. For example, “ . . you never hear anyone impugn white New Englanders like the Kennedys, John Kerry, or Howard Dean for saying “idear” instead of “idea,” yet “aks” in place of “ask” is somehow indicative of all kinds of negative things” (Tumblr) There is a stigmatization on students whose linguistic and cultural background is seen as poor, uneducated, and unrefined. The United States is a culturally and linguistically diverse country yet standardized testing refuses to acknowledge that.

James Paul Gee discusses Discourse to answer the question, “why do so many poor and minority students fail in school?” He mentions that “there was a mismatch between the language practices of certain sorts of children’s homes and the language practices of school.” According to Gee, language has much more to do with social and cultural contacts in which it is used; socially situated identities. English language learners have to combat numerous difficulties, often adjusting to their new surroundings, acculturation, learning conversational and academic English and content at a rapid pace, being subjected to various forms of racism, possible personal and family issues, a possibly low economic situation, stigmatization, unfair testing and harsh sanctioning.

NCLB’s increased accountability only hurts ELLs and minorities who are disproportionately low-income and are more likely to attend lower-resourced schools.

This is a kick-them-while-they’re-down system. In a comment to a NY Times Room for Debate post, Marcelo Suárez-Orozco and Carola Suárez-Orozco respond to the question, “what do school tests measure?” with “the current high-stakes testing and accountability systems create unintended consequences for immigrant English-language learners, which outweigh whatever benefits standardized tests may have. Because too many immigrant students attend highly segregated and impoverished schools, are not exposed to quality curricula and undergo multiple school and programmatic transitions, their performance on such tests is often compromised."“Schools which receive Title I funding through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 must make Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) in test scores (e.g. each year, its fifth graders must do better on standardized tests than the previous year's fifth graders).If the school's results are repeatedly poor, then steps are taken to improve the school.Schools that miss AYP for a second consecutive year are publicly labeled as being "in need of improvement" and are required to develop a two-year improvement plan for the subject that the school is not teaching well. Students are given the option to transfer to a better school within the school district, if any exists.Missing AYP in the third year forces the school to offer free tutoring and other supplemental education services to struggling students.If a school misses its AYP target for a fourth consecutive year, the school is labelled as requiring "corrective action," which might involve wholesale replacement of staff, introduction of a new curriculum, or extending the amount of time students spend in class.A fifth year of failure results in planning to restructure the entire school; the plan is implemented if the school fails to hit its AYP targets for the sixth year in a row. Common options include closing the school, turning the school into a charter school, hiring a private company to run the school, or asking the state office of education to run the school directly” (Wikipedia).

They go on to say, “not only are many immigrant children tested before their academic language skills have adequately developed, but all too often their day-to-day educational experiences are shaped by instruction that teaches to the test, which is far from an adequate measure of what it takes to succeed in the complex and challenging economies and societies of the 21st century. This eye on the omnipresent ‘adequate yearly progress’ is more often than not at the expense of more engaging, broader academic knowledge. What’s more, this test regime has huge implications for dropout rates as well as college access for children of immigrant families.”

With these kinds of sanctions threatening students and teachers, it is no wonder why there is high test anxiety. The stigmatization in labelling schools and subsequently the students themselves is cause for a decrease in confidence. Students who want to perform well might feel under-prepared or insecure. The threat of firing teachers or closing the school entirely can give a student a sense of dread. It is stress inducing so while students are in class, being taught test taking skills with an emphasis being put on the importance of high scores, students lose focus of the content of the instruction on focus solely on the importance of the test. While taking the test, student’s might “psych themselves out” or “go blank” because of the excessive significance placed on the test.

With these kinds of sanctions threatening students and teachers, it is no wonder why there is high test anxiety. The stigmatization in labelling schools and subsequently the students themselves is cause for a decrease in confidence. Students who want to perform well might feel under-prepared or insecure. The threat of firing teachers or closing the school entirely can give a student a sense of dread. It is stress inducing so while students are in class, being taught test taking skills with an emphasis being put on the importance of high scores, students lose focus of the content of the instruction on focus solely on the importance of the test. While taking the test, student’s might “psych themselves out” or “go blank” because of the excessive significance placed on the test.For English language learners, taking a standardized test is accompanied with even more worries. In addition to the aforementioned stressors all students are facing with high stakes testing, ELLs must also employ their new understanding of the English language and interpret complicated test language solely by reading (this can be especially detrimental to ELL students who benefit from auditory cues to understand English). They must consider the individual implications of failing such as not being allowed to graduate entirely based on the test score completely disregarding how well the student did in school. High stakes testing, being a cause for anxiety and stress, and failure of the test can lead to low self esteem, loss of interest in school, and drop-out.

The American education system as been called the “anti-model” for how to do school reform by Larry Booi and J.C. Couture in their article "Testing, Testing," in which they compare their Canadian education system with the United States'. “By contrast we can also learn what not to do from reform in the US, whose education system is in decline. Its elements, implemented over the past two decades, are largely ideological: “market-based” reforms (the application of “business insights” to the running of schools); an emphasis on standardization and narrowing of curriculum; extensive use of external standardized assessment; fostering choice and competition among schools, often with school vouchers; making judgements based on test data and closing “failing schools”; encouraging the growth of charter schools (which don’t have teacher unions); “merit pay” and other incentives; faith that “technologically mediated instruction” will reduce costs; an overwhelming “top-down” approach which tells everyone what to do and holds them accountable for doing it.”

Canada, and other accompanying countries who have consistently outperformed American students, it seems, has detailed exactly what we should not be doing and is successfully modeling what we should be doing instead, including:

1. Funding schools equitably, with additional resources for those serving needy students

2. Paying teachers competitively and comparably

3. Investing in high-quality preparation, mentoring and professional development for teachers and leaders, completely at government expense

4. Providing time in the school schedule for collaborative planning and ongoing professional learning to continually improve instruction

5. Organizing a curriculum around problem-solving and critical thinking skills

6. Testing students rarely but carefully -- with measures that require analysis, communication, and defense of ideas (Jennings).

Annual high stakes standardized testing does not improve education. The accountability and drastic sanctions for failure of these tests most certainly do not help the matter. Major educational decisions should not be based solely on test score. The additional hardships standardized tests force upon English language learners contributes to the achievement gap between race and language minorities perpetuating social injustices to their community. Standardized tests as one way to measure student’s progress is acceptable if it coincides with other various assessment models and without the high stakes accountability.

No comments:

Post a Comment